Dear Fellow Caucasians, Let’s Stop Using The Term ‘Colorblind’

Last week’s controversy surrounding Hellboy’s executive producer Christa Campbell wasn’t so much of an eye-opener as it was a reminder that, despite the onslaught of articles, op-eds, and tweets we read daily surrounding race, the willingness to ignore the conversation permeates every level of society and influence.

“Stop projecting your own sh*t onto us. We are all one. We don’t see colors or race,” said Campbell in a now deleted tweet, defending the casting decision of Ed Skrein, a non-Asian actor, to play Japanese-American Ben Daimio.

Campbell’s sentiments aren’t innocent — after all, she holds a position of power that actively plays a part in taking away a role from an actor of color. The term she used, however, may strike a chord with many well-meaning White people; after all, doesn’t her “colorblindness” mean that she sees people for who they are as individuals and not their race? Isn’t that what we’re supposed to do? Isn’t that what non-Whites want? To be treated as people first, race second?

From my heart of hearts, I get it — unless you’re a casting director or executive producer, you mean well. I see it. It’s a term that comes from a non-hostile place, and one with good intentions, but it’s really time to put it out to pasture; it does a disservice to the people of color that you care about.

Back in college, I paid my bills by nannying for a few different families. One of those families was composed of White parents, two adopted Black children, and one biological White son. I’d never nannied for non-White children before, so I thought that the best way to approach the job was to treat them no differently than I would White kids. In theory, this is absolutely what one should do — these children are equal in value to any other child — but in practice, I started to see where I was failing the adopted kids.

One day, four-year-old Tasha* came home from a friend’s house, clearly upset. “What’s wrong?” I’d asked.

“Penny* said I was Black,” Tasha said, frowning.

I was a little taken aback, completely unprepared for what she had just reported. “What did you say to Penny?” I asked, choosing my question carefully.

“I told her that I wasn’t Black. I’m tan,” she said, pointing to her arm.

Tasha had a point — I knew her birth mother had been White and her birth father had been Black, and without having the cultural connection of growing up in a Black family, there was really no reason for her to think that she was anything other than slightly darker than her 100% pale peers. Growing up in a White family and predominately White community meant that she had no context for her physical features. In her own eyes, she was Tasha: a four-year-old girl who liked princesses, horses, and stickers and was slightly darker than her mom, dad, and one of her brothers. To everyone else, she was Black.

Not knowing how to handle the situation in a way that would both help her and be agreeable to her parents, I promised that, if it bothered her a lot, we could bring it up with her mother later. That seemed to appease her and she ran off to play with her brothers.

Later that evening, I explained what had transpired to her mother. I’ll never forget what she said:

“This isn’t the first time this has happened; I’ve spoken with Penny’s mom about this before, and she says her kids are colorblind and don’t see race.

“I don’t believe in this colorblindness bullsh*t. Children see race — they just don’t know it yet. If my kids ever say anything about race, please tell me. I need to know how they’re processing this. I am trying my best to help them but I can’t do that if I don’t know how they’re thinking about it,” she said with the raw sincerity full of a mother’s love.

And it was true, she was trying to help her children. She bought her daughter Black barbies, learned how to properly do hairstyles for Black hair, and enrolled her children in schools with more diversity — even though it cost the family more. TV shows with Black characters were actively encouraged, and the children openly discussed their adoption stories with their parents in a healthy manner.

It was in that moment that I realized how damaging the term “colorblindness” can be; when someone says it, they mean to convey that they see a person of color for who they are as an individual and not as their race. But by saying it, we, with good intentions, erase a part of someone’s identity, as if the absence of race is to be praised, putting down efforts for that person to express who they are.

After that talk, I became more acutely aware of how often Tasha spoke about race. She regularly told me how the kids in her family were tan but her parents were not. How she felt the need to correct people who called her Black. Saddest of all, if a Black person was on the news for a crime, she would often point to her own skin, finding a rare commonality of a real person who matched her color. “That man who kidnapped those kids? He’s tan, like me,” she said, speaking about a recent event as we drove home from dance class one day. “They’re always tan.”

Her mom stopped watching the news with the kids around after that, lest her children think that criminals best represented their skin color.

Tasha didn’t grow up in a Black family with the same understanding of her ethnicity as other Black children, but she talked about race before she even knew what race was. She knew she was different than those around her, but seemed unaware as to the extent of those differences and what that meant for her in society. All she knew was that her skin color was slightly darker than the rest, and while she recognized it was important, she didn’t quite understand how that fit in with her identity. She was just Tasha. But she was also tan.

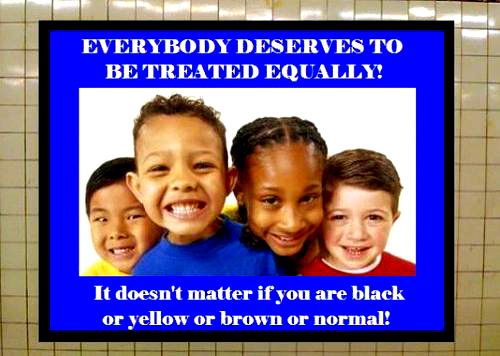

Tasha was about four years old when she first saw race; in contrast, I was seventeen. In fact, I remember the exact moment I saw race — this image:

I thought about this “motivational poster” for a long time, at first not sure why I laughed so hard at it. Was Whiteness normal? Did that make non-Whites abnormal? Why was that so absurdly humorous to me? Why did it resonate with me so hard?

And then it hit me — up until that point, Whiteness had been what I perceived to be normal. A Black woman or an Asian man were simply White (normal) people with an exotic flair or interesting twist. They had the same problems I had, like wondering what to major in in college or struggling with family relationships, but any issues outside of that, such as feeling othered for the color of their skin or being from another country, weren’t… normal.

Weren’t White.

I realize now what “colorblindness” is supposed to mean — by replacing the word “White” with “normal”, we as White people make equality more palatable. I believe that the majority of us want to treat non-Whites as equals, like one of us. But for some reason, it only seems possible if we excise the “uncomfortable” issues people of other racial groups have. When we remove their histories of oppression, maltreatment, and grievances against us, we feel that the playing field is leveled. We breath a collective sigh of relief; now we can hold conversations with them about their weekend or how their kids are doing in school without having to think about how their racial background might play into their lives. We’ll talk about it if it’s of potential value to us, sure — tell us how your mom makes delicious adobo or teach us a curse word in your language. But start in on something negative and we’re suddenly “colorblind”.

Colorblindness, therefore, is a piss-poor cop-out asking for non-Whites to make an attempt to “be normal”.

To be White.

Fellow White people, I write this knowing that the majority of you mean well. You’re not a White supremacist for trying to see past race and just focus on the good in people. I know that’s our go-to response. We say this through proverbial clenched teeth and beads of sweat dripping from our forehead, afraid of being accused of racism as we try to paint ourselves as one of the righteous ones. For the past few years, you may have felt increasingly more upset at the cultural conversations that are happening all around you — not always about you, but never without you — as people of color shout from the rooftops what it means to be them in a society that doesn’t always make them feel welcomed.

To you, I say, I get it. I see you. Your effort to treat another person as an individual comes from a good place.

But it’s time to be honest with ourselves.

Campbell may think that she’s being a good person by being “colorblind”, but truthfully, it’s not possible. We see a person’s skin color or eye shape before we see their personality. We see a person’s sex or gender before we see their capability. And we see a person’s ability or physical limitations before we see their sense of humor. In our attempt to claim that we see past that, we insult the people we’re trying to equalize. We’re ignoring not only a huge part of their identity, but their struggles with accepting themselves in a society that would otherwise be grateful for them to not exist.

We need to acknowledge color and can do so without it being negative — we can celebrate differences and how they’ve shaped someone of another race into the person they are.

Ben Daimio’s Japanese heritage shaped his character; by being “colorblind”, we’ve erased a huge part of his identity.

They say art imitates life — by being “colorblind”, do we ask the same of our non-White peers?

Let’s do better.

Let’s see color.

Let’s end “colorblindness”.

*names have been changed to protect identities.

Share this Article

Share this Article