Inside Aokigahara, Japan’s Infamous Suicide Forest

Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge. Golden Gate Bridge. Prince Edward Viaduct. Aokigahara Forest. What do these things have in common? They’re the most common places for people to commit suicide.

The difference between Prince Edward Viaduct and the other two bridges, however, is that Canada built the Luminous Veil, or a barrier consisting of thousands of steel rods, to prevent further suicides. And while the U.S. and China can follow suit with their deadliest locales, Japan’s Aokigahara — better known as suicide forest — is finding prevention more difficult.

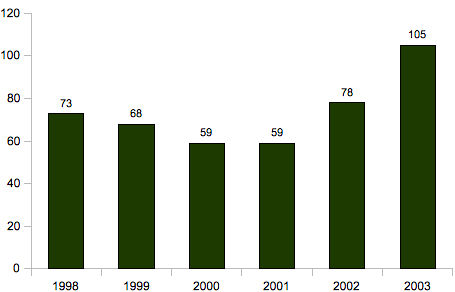

Aokigahara, also called the “Sea of Trees”, has a mysterious, eerie feel to it. For those who believe in spirits, they may feel inclined to attribute the haunting stillness to the souls of those who have taken their own lives, destined to haunt the forest for eternity. These woods are not wanting for lost souls — since the 1950s, salarymen intent on ending it all have entered Aokigahara to never be seen again. In 2003, 105 bodies were recovered from the forest, beating the previous record-breaking year of 78 in 2002. In an effort to prevent further suicides, this would be the last year the Japanese government released any information regarding the suicides to the public.

Most of the suicides are reported to occur during March, at the end of Japan’s fiscal year. It is during this month that many companies evaluate their finances and determine whether or not they can afford to keep employees.

That’s what happened to Taro, a man who wished to only be identified by his first name. He purchased a one-way ticket to Aokigahara after losing his position at a manufacturing company, his life in shambles after overwhelming debt piled up. “My will to live disappeared,” he said. “I’d lost my identity, so I didn’t want to live on this earth. That’s why I went there.”

After arriving in the Sea of Trees, Taro slit his wrists. The wounds were shallow, so he wandered around for several days, waiting for death to take him.

Starving, dehydrated, frostbitten, and weak from blood loss, Taro collapsed in some bushes, death quickly becoming him. Fate intervened, however, when a hiker stumbled across his near-lifeless body and got him the help he needed.

Taro would lose his toes on his right foot due to frostbite, but he would survive.

Japan’s suicide rate — one of the highest in the world — is increased by societal factors, such as job insecurity and finances, with men between the ages of 20 and 44 being more likely to die of suicide than any other method. “Unemployment is leading to this,” said Toyoki Yoshida, a suicide and credit counselor. “Society and the government need to establish immediate countermeasures to prevent suicides. There should be more places where they can come and seek help.”

Yoshida and other volunteers have dedicated their time to posting signs around the forest, urging those desperate to take their own lives to call their organization instead. In their eyes, Japanese society often looks down on the jobless and bankrupt, and suicide seems like the most honorable — sometimes only — option.

Local authorities have also posted signs throughout the forest. One sign reads “Your life is something precious that was given to you by your parents”; another, “Meditate on your parents, siblings and your children once more. Do not be troubled alone”. Cameras are also posted at the entrances to the forest in an effort to track all those who go in, with officials knowing that not all will re-emerge; they are also tasked with the gruesome duty of sweeping the woods for bodies each year, before the holiday season, and identify remains when possible.

“Especially in March, the end of the fiscal year, more suicidal people will come here because of the bad economy,” said Imasa Watanabe of the Yamanashi Prefectural Government. “It’s my dream to stop suicides in this forest, but to be honest, it would be difficult to prevent all the cases here.”

With Logan Paul’s latest debacle, he incites a fear that Aokigahara will be further romanticized by those who seek death, with officials sternly disavowing the notion. “I’ve seen plenty of bodies that have been really badly decomposed, or been picked at by wild animals… There’s nothing beautiful about dying in there,” warned a local officer.

A year after his suicide attempt, Taro, still jobless and homeless, often feels the allure to commit suicide but has determined to carry on. “I try not to think about it, but I can’t say never. For now, the will to live is stronger.”

If you or anyone you know is suffering with thoughts of suicide, please contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

Share this Article

Share this Article